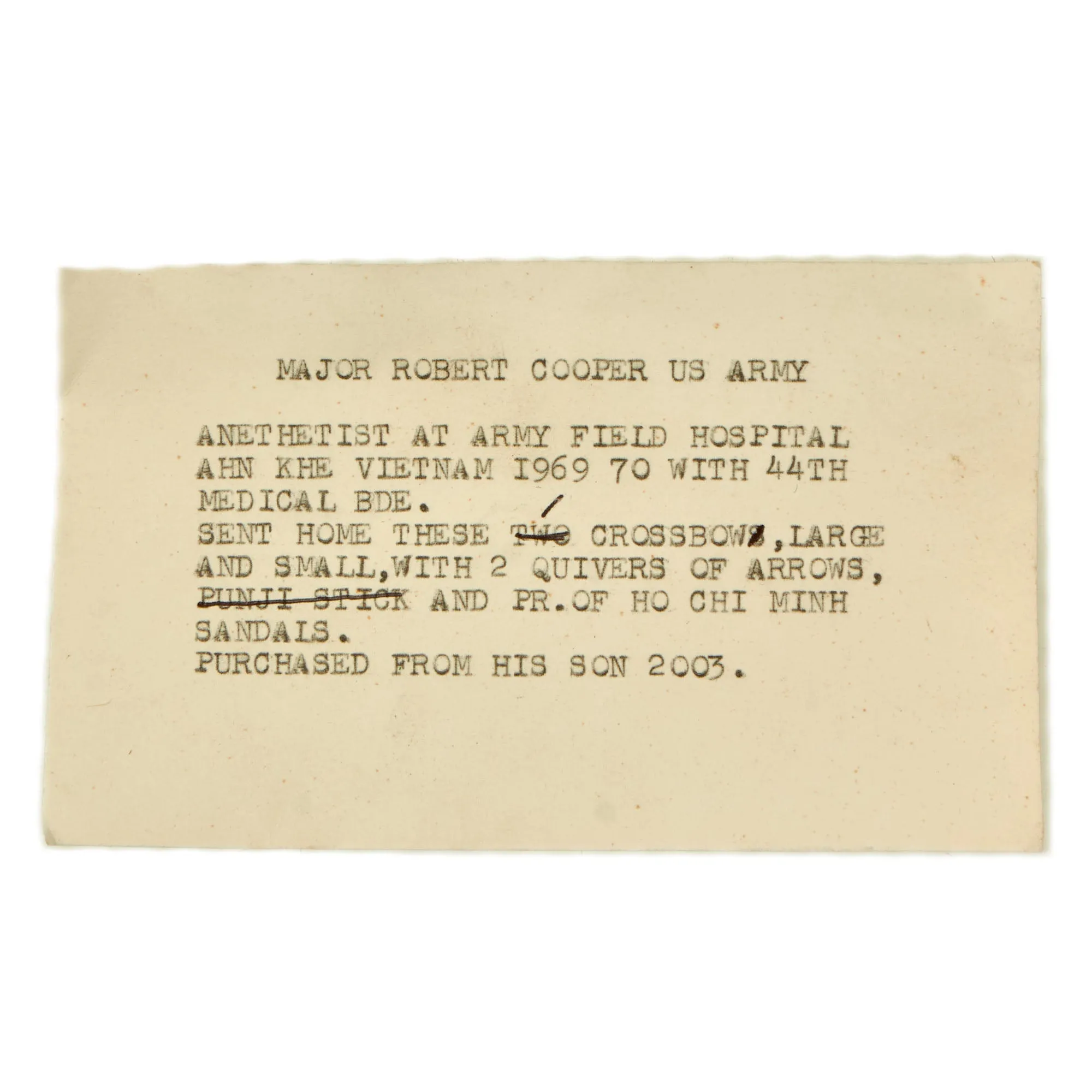

Original Items: Only One Available. Genuine USGI bring Backs from the Vietnam War. This hardwood crossbow was the weapon of choice for the indigenous Montagnards. Features original lathe, with no damage or repairs. The original trigger mechanism has however been lost with cracking present where it was. The bow measures 20 ½ inches and the body measures 11 ⅜ inches long , making a fantastic display. Also included are 2 quivers full of original bolts or quarrels. There are at least a dozen.

A quarrel or bolt is the arrow used in a crossbow. The name "quarrel" is derived from the French word carré, meaning square, referring to their typically square heads. Although their lengths vary, bolts are typically shorter than traditional arrows.

Ho Chi Minh sandals are iconic for having been worn by the Vietcong during the Vietnam war. During the war they were considered by many more practical than army boots, because being open they allowed the foot to dry and thus prevented the onset of ‘jungle rot’. But what makes Ho Chi Minh sandals really special was the simplicity and effectiveness of their design.

This pair of 'Ho Chi Minh' sandals is made from recycled rubber. The soles of the sandals are made from discarded car tires and the top straps are made from inner tubes.

Rubber automobile tire sandals were used extensively by Viet Cong forces during the Vietnam War. They were inexpensive to make and proved a practical alternative to boots in the humid climate of Vietnam.

The construction and fit of these Vietnamese sandals is fascinating:

First, none of the straps are glued or nailed, they stay fixed in the sole only because of the tight fit and the rubber grip. This means that with a little effort the length of each strap can also be adjusted to fit the individual users foot width.

Second, the elastic ‘crossed’ ankle straps provide a surprisingly secure fit around the

ankle. The secure fit and added support of the ‘crossed’ straps is ideal for running and moving quickly.

This set was sent home with the crossbow and is offered in very good condition, with some original period dirt still on them! They look to be fully functional, and both measure about 9 1/2 inches in length.

Both come more than ready for further research and display.

The Degar, also known as Montagnard, are the indigenous peoples of the Central Highlands of Vietnam. The term Montagnard means "people of the mountain" in French and is a carryover from the French colonial period in Vietnam. The term "Degar" is generally used only by people connected with Kok Ksor and the Degar Foundation. Most of those living in America refer to themselves as Montagnards, while those living in Vietnam refer to themselves by their individual tribe.

The Vietnamese tribesmen who fought alongside American Special Forces won the Green Berets’ admiration—and lost everything else.

In 1965, syndicated columnists Rowland Evans and Robert Novak used a frontier metaphor to describe the American Special Forces’ advisory role with Vietnamese tribesmen. “Assume that during our own Civil War the north had asked a friendly foreign power to mobilize, train, and arm hostile American Indian tribes and lead them into battle against the South,” they wrote.

"If that historical hypothetical suggested wild possibilities, Evans and Novak used it advisedly. For four years, Special Forces had been training an oppressed minority group in guerrilla tactics, providing them with weapons and acting as de facto aid workers in their communities. When Americans remember Vietnam, we often think of the war as having three major actors: the North Vietnamese, the South Vietnamese, and the American military. But there was another player: the Montagnards.

The indigenous Montagnards, recruited into service by the American Special Forces in Vietnam’s mountain highlands, defended villages against the Viet Cong and served as rapid response forces. The Special Forces and the Montagnards—each tough, versatile, and accustomed to living in wild conditions—formed an affinity for each other. In the testimony of many veterans, their working relationship with the Montagnards, nicknamed Yards, was a bright spot in a confusing and frustrating war. The bond between America’s elite fighters and their indigenous partners has persisted into the present, but despite the best efforts of vets, the Montagnards have suffered greatly in the postwar years, at least in part because they cast their lot with the U.S. Army. In a war with more than its share of tragedies, this one is less often told but is crucial to understanding the conflict and its toll.

The Montagnards, whose name is derived from the French word for mountaineers, are ethnically distinct from lowland, urban Vietnamese. In the early ’60s, writes military historian John Prados, almost a million Montagnards lived in Vietnam, and the group was made up of about 30 different tribes. The Montagnards spoke languages of Malayo-Polynesian and Mon Khmer derivations, practiced an animistic religion (except for some who had converted to Christianity), and survived through subsistence agriculture.

When the United States Special Forces first arrived in Vietnam in the early 1960s, the Montagnards were already decades into an uneasy relationship with Vietnam’s various central governments. Before their withdrawal, the French had promised to give the Montagnards protected land—a promise that vanished with them. The Communist government of North Vietnam had included the right for highlander autonomy in its founding platform in 1960, but many Montagnards were uneasy about Communist intentions. Meanwhile, South Vietnam’s President Ngô Đình Diệm had begun to settle refugees from North Vietnam in the highlands. His government neglected education and health care in the Montagnard areas, assigning inexperienced and ineffective bureaucrats to handle their needs.

Tensions between the Vietnamese and the Montagnards were ratcheted up by racism. Vietnamese called the tribal people mọi, or savage. Prados recounts a story of a “young Vietnamese woman who told an American, in all seriousness, that Montagnards had tails.” Stereotypes about the “primitive” nature of the tribesmen—unfounded beliefs that they were all nomadic and lived by slash-and-burn farming—made it easier for the government to advocate the expropriation of their lands.

Starting in 1961, in an initiative at first run by the CIA, the Special Forces moved into the Vietnamese mountains and set up the new Village Defense Program (a forerunner of the better-known Strategic Hamlet Program). The Montagnards’ forested mountain homelands, which ran along the Cambodian and Laotian borders in the western portion of Vietnam, were prime highways for North Vietnamese forces to move men and materiel. The Viet Cong, understanding the way the Southern government discriminated against the tribes, promised much if the tribesmen would defect—and some did. But the VC also preyed on isolated villages, taking food and pressing Montagnards into labor and military service.

The working relationship between Green Berets and Montagnards began in the Village Defense Program. Detachments of 12 Green Berets trained Montagnards, drawn from the tribe dominant in the surrounding area, into “civilian irregular defense groups,” or CIDGs. The idea was that a security zone would radiate outward from each camp, with CIDG serving as defense forces, advised by small groups of American Special Forces and South Vietnam’s own special forces, the LLDB. With help from the Navy’s Seabees, Special Forces built dams, roads, bridges, schools, wells, and roads for Montagnard groups, and Special Forces medics provided rudimentary health care. By December 1963, 43,000 Montagnard defenders guarded the area around the first camp, Buon Enao, from the Viet Cong, while 18,000 Montagnards were enlisted in mobile strike forces, which were deployed by air to spots where conflict broke out.

The Green Berets also admired the Montagnards’ fighting prowess, noting their loyalty. As Bridges told an interviewer, the Green Berets believed that “the Montagnards made excellent soldiers.” They were used to working in teams: “They were very good at small unit tactics and seemed to know instinctively how to protect their flanks. In a way, combat was almost like a family situation with them: you protect your brother and your brother protects you.” Bridges added, “I found them very brave under fire. They wouldn’t hesitate to run out and help a team member who was in trouble.”